- Messages

- 200

- Points

- 97

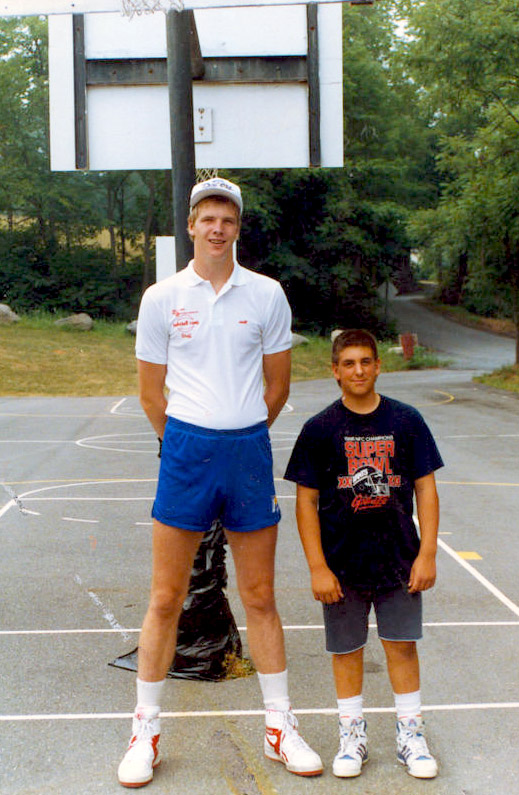

- Height example: 6'2

- 6'1"

- Shoe

- 13

He discusses height a lot.

http://theclassical.org/articles/giant-size

Giant Size

Paul Wight and The Air Up There

Edouard Beaupré was the giantest giant in pro wrestling history. At eight feet and three inches, Beaupré was the fifth-tallest human being in recorded history, and he wrestled at a time when wrestling was pretty much just big strong guys fighting each other at carnivals. Before Beaupré's pituitary gland really started acting up, he'd wanted to be a cowboy, but his size kept him from riding horses. So instead, he lifted them, squatting down and lugging around 800-pounders at circus sideshows across North America. And on at least one occasion, he wrestled fellow strongman Louis Cyr and, by most accounts, got his ass resoundingly beat.

Beaupré was 23 and still growing when he died of tuberculosis in St. Louis, though the gigantism that kept him growing probably didn't help. His family didn't have enough money to bring his body back home to Saskatoon, and the circus wasn't going to pay it. Instead of burying him, the kind circus folk embalmed Beaupré and used his body as an attraction. Even in death, Beaupré lived as a freak.

Paul Wight, better known as the Big Show, has been pro wrestling's reigning giant for the better part of two decades, and he's never heard of Beaupré. But Wight is well acquainted with the idea of the tragic giant. Talking on the phone from Denver, a few hours before he crushes Chris Jericho's back in a ladder on Monday Night Raw, Wight says, "I catch shit from my wife every now and then. I start talking about how giants don't live very long, and she gets hot at me." He doesn't seem especially concerned about it.

***

If you read Jordan Conn's Roy Hibbert profile on Grantland a couple of months back, you learned a striking statistic: According to the Center for Disease Control, if you are seven feet tall and between the ages of 20 and 40 in the U.S., you are in very select company; there are fewer than 70 people like you. Ever since February, when he turned 41, Wight hasn't been one of the 70, but he's spent almost his entire professional life among their number. The WWE likes to call Wight "the world's largest athlete," and for all I know they're right. But he has competition.

If you're huge and athletic, you probably play basketball, the sport where all that height has the most obvious uses. Wight wanted to play basketball until he figured out that even giants need some vertical leaping ability. That hasn't stopped others, though. In NBA history, plenty of titans have soared (Wilt, Kareem, Shaq), and plenty others have become punchlines (Shawn Bradley, Hasheem Thabeet, Gheorghe Mureşan). And the giant failures often tend to be more interesting than their successful peers; just imagine a hangdog Bradley mooning around an NBA locker room, bumping Garth Brooks on his Discman, utterly failing to make any non-paralyzingly-awkward conversation with his teammates.

If you want to fall down a real Wikipedia hole, though, start looking into the seven-foot athletes who found their way to other sports. Consider, for example, the South Korean kickboxer and MMA fighter Choi Hong-man, or Pakinstani cricketer Mohammad Irfan. The 27-year-old, 7'1" pitcher Loek van Mil is the tallest professional baseball player ever, and he's currently playing for the Akron Aeros, one of the Cleveland Indians' AA farm teams. These are people who did strange things with their even stranger genetic birthrights.

When someone that tall enters competitive public arenas, their humiliations are that much more visible: Tracy McGrady bringing God's fire down on Shawn Bradley is a YouTube classic. So is the sight of Emelianenko Fedor submitting Hong Choi-man by grabbing an armbar and holding onto it for dear life, like a farmer hugging a tree limb in a tornado. But those moments of operatic mortification have nothing on sports' actual tragic-giant stories, which will make your heart hurt if you let yourself think about them. 7'2" Margo Drydek, the tallest player in WNBA history, dead at 37 after suffering a severe heart attack, while pregnant with her third child. 7'11" Romanian boxer Gogea Mitu, dead of tuberculosis at 21. Argentine pro wrestler Jorge González, who wrestled as the Giant González in the WWF and El Gigante in WCW, dead of diabetes at 44. In sports, as elsewhere, the tallest among us do not last. The human body was not meant to reach the heavens.

***

By most accounts, Bill Walton stands well over seven feet tall. But during his NBA career, Walton always insisted that he was 6'11" because he didn't want to be considered a freak. When I read that fun fact in David Halberstam's The Breaks of the Game, it hit a chord. I've been doing the exact same thing as Walton for my entire adult life. I'm not as tall as Walton. I'm not even one of the less-than-70 seven-footers in my age bracket in the U.S. But I'm close. Another quarter-inch, and I'd pass the seven-foot barrier. But anytime anyone asks my height, I say that I'm 6'11". I don't mention the extra three quarters of an inch. People don't need to know about that.

In any case, I'm still pretty fucking tall. And being pretty fucking tall is a weird thing to wrap your head around.

In my life, I've met four people taller than me, and I remember each one of them vividly. The one guy outside the bar in Baltimore who wanted to talk about the Gaslight Anthem. The backup center for the Syracuse Orangemen, who I saw around campus for four years and then only talked to when I drunkenly photobombed him during a graduation party. The frighteningly skinny African man with the two chipped front teeth who stood in front of me in line at a Seattle coffeehouse. The goateed yokel who, in a cruelly appropriate twist of fate, ended up standing directly in front of me during the Ramones' set at the West Virginia stop of Lollapalooza 96. Every time I met one of them, I felt a sharp wave of vertigo. The experience of looking up to talk to somebody just felt so completely alien every single time. Looking up is not a thing that I do.

When you're this tall, it becomes a deeply entrenched part of who you are. You become separate, or at least you think of yourself that way. At loud parties, you need to find a stool if you want to hear anything anybody says; otherwise, you're a disembodied head floating a foot above the crowd. Your clothes will not fit as well as other people's clothes, and you will be acutely aware of that fact at all times. In certain American cities, large crowds of children will just bust up laughing when they see you coming. (Baltimore, you are forever my home and I love you, but sometimes fuck you.) And if you spend enough time looking at the Wikipedia pages of past famous giants, you will start to think of yourself as doomed.

On the other hand, people remember your name, it's easy to get bartenders' attention, and you can almost always see well at concerts, though your sightlines usually come at somebody else's expense. It's a bargain that your genetics made for you.

***

Paul Wight, bless him, seems to think of his massive size as a gift from God, not a devil's bargain. There was a moment earlier this year when Wight was rumored to be fighting Shaq at this year's Wrestlemania. If that had happened, it would've been the collision of the two most genially cartoonish giants in sports, the two guys who come off most like enormous eight-year-olds. I wanted to talk to Wight for this piece because, among the giants I've seen on TV, he seems the least tortured by his height. After all, he's voluntarily spent the last 17 years in a grandly ridiculous, mortally dangerous line of work -- strapping on his comic-book caveman singlet and pretending to fight hulking musclemen across the globe, risking crippling injury every time he lets one of them lift him.

There are plenty of reasons why I could never do what Wight does. Even though we're nearly the same height, he weighs more than two of me. And the two afternoons I spent in a pro-wrestling training ring a decade ago taught me how much it hurts to wake up the morning after you've been learning to theatrically flop on canvas. But mostly, I've never been able to imagine performing my height. I've gotten used to people staring at me, but I've never learned to like it. I played basketball in high school, but I sucked at it, and hated sucking at it. I never bothered to learn how to play the game effectively beyond the obvious lumbering rebounds and shot-blocks. I fouled out of games on purpose if I was in a bad mood. I told myself that I wanted to do something with my brain and not my body, like that was even my choice to make, or like there was any real divide. So now I'm a writer, and I spend entire days living in my own head, only leaving to take my dog on walks or to take my kid to the park. Truthfully, I was too lazy and too self-conscious to ever do jack shit athletically. I'm a writer because it's what I've always wanted to be, but god knows my height probably had something to do with that desire. Pro wrestling is pretty much the opposite of anything I could ever do. I am not like Paul Wight.

***

Wight's always been huge. By his own estimation, he was nearly five feet tall at five years old. But he looks comfortable in his skin, and he says that he's been at peace with it ever since high school. "There was some awkwardness to it when I was very young, but I came to rely on it, to make it a strength," says Wight. "I embraced my size."

He's not wrong. For the past few generations of wrestling fans, Wight has been an affable constant, one of the few guys who never goes away. Wrestling lore is filled with giants like the Great Khali and the Giant Silva and Kurrgan, massive human redwoods who had a few memorable moments but who faded into the background as soon as everyone realized they couldn't really wrestle. Wight can wrestle, and he can do all the intangible non-wrestling things that pro wrestlers need to do. He can loom. He can glare. He can act, after a fashion. He can, when necessary, abase himself, or mercilessly mock himself. He can grow a mean mullet. He can convincingly appear to get his ass beat by Floyd Mayweather at Wrestlemania.

When Wight realized that the NBA wasn't going to work out for him, he spent a few years working civilian jobs: "I was a used car salesman for a little while in Wichita, Kansas, and I answered the phones for a company in Chicago called Jusco Karaoke. I tried to be a door-to-door salesman for State Chemical Manufacturing; that didn't work out." But he's always been a wrestling fan, and after a meeting with Hulk Hogan, he finally found a way to break in. In his first-ever match in 1995, he beat Hogan for the WCW World Championship. He's been around ever since.

Many of the vocal internet fans of pro wrestling love to hate Wight, since he regularly obliterates their underdog favorites and since he never busts out the same spectacular moves as his smaller peers. But to hear Wight describe it, his vast and glacial ring presence is something he had to learn: "When you have size and ability, you can't do all the things that you're capable of because it just doesn't make sense. Yeah, I can do a moonsault, I can do a dropkick off the top. But a lot of these moves, the promoters will tell you that it just doesn't make sense for our industry. You're supposed to be a big guy, stand in the middle, let people bounce off of you. When I was starting out in the industry, my size was an attraction, and I wanted to be an athletic attraction. I wanted to wrestle as hard as the other guys. But visually, it just doesn't look right for the big guy to do the same things as the smaller guys. Our business is to entertain, so I had to learn a role and fill that role."

I mention last year's Survivor Series. During a match against the former Olympic weightlifter Mark Henry, Wight climbed to the top rope and then jumped off, hitting Henry with a titanic diving elbowdrop. But before leaping, Wight teetered on that top rope for a few seconds, looking like he was having second thoughts about what he was about to do. It's exactly how I imagine I'd look if I found myself on the top rope. "That was all drama," says Wight. "If I just walked up there and made it look easy, it wouldn't be as dramatic as it was."

***

Wrestlers have long histories of dying young, of suffering debilitating injuries, of finding it impossible to make their personalities translate on the required grand scale. Wight has endured, and along with Andre the Giant, he's really one of only two giants in pro-wrestling history who can claim that.

Andre was, of course, most famous giant in wrestling history. Andre owed his size to acromegaly, the pituitary condition that ultimately led to his death. Wight was also born with acromegaly, but it doesn't look like it's going to kill him. When Wight was 19, he went into the Mayo Clinic for surgery to keep him from growing further. He apparently suffers no further ill effects from the condition. (Other famous acromegaly cases: The Addams Family star Ted Cassidy, two-time James Bond bad-guy henchman Richard Kiel, Tony Robbins, possibly Abraham Lincoln.) Wight's fellow current WWE giant, the 7'1" Great Khali, also has acromegaly, and he just had his own height-ending surgery.

According to Wight, it helps that he works with the WWE's crack medical professionals at his disposal. But I still hear plenty of black humor coming through when he's talking about his acromegaly: "I'm actually doing really good. Unless I walk out in front of a bus -- a really big bus -- I have the chance to live a really good life... I'd like to live to be the first old giant. That would be cool."

***

My son was born a month ago, and he is going to be tall; there's no getting around it. My wife is six feet tall, and my height combined with hers is a genetic combination that practically guarantees tower status. He could be taller than me. I feel a little bit sorry for the guy.

Wight has kids, and they're tall. But they're not freaky-tall; they're regular-tall. I ask him if he was ever worried about passing his size onto his kids, and he gives me a sitcom-dad line about fearing the day his daughter starts to date.

Wight's wrestling career has been exceptionally long and important, and that's amazing. But what's even more amazing is that he seems to be a rare beast: A giant with absolutely no evident self-consciousness, no crippling constant awareness that he is not like others. For a select few of us, that makes him an inspiration.

http://theclassical.org/articles/giant-size

Giant Size

Paul Wight and The Air Up There

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

AUGUST 13, 2012 - 8:54AM | BY TOM BREIHANEdouard Beaupré was the giantest giant in pro wrestling history. At eight feet and three inches, Beaupré was the fifth-tallest human being in recorded history, and he wrestled at a time when wrestling was pretty much just big strong guys fighting each other at carnivals. Before Beaupré's pituitary gland really started acting up, he'd wanted to be a cowboy, but his size kept him from riding horses. So instead, he lifted them, squatting down and lugging around 800-pounders at circus sideshows across North America. And on at least one occasion, he wrestled fellow strongman Louis Cyr and, by most accounts, got his ass resoundingly beat.

Beaupré was 23 and still growing when he died of tuberculosis in St. Louis, though the gigantism that kept him growing probably didn't help. His family didn't have enough money to bring his body back home to Saskatoon, and the circus wasn't going to pay it. Instead of burying him, the kind circus folk embalmed Beaupré and used his body as an attraction. Even in death, Beaupré lived as a freak.

Paul Wight, better known as the Big Show, has been pro wrestling's reigning giant for the better part of two decades, and he's never heard of Beaupré. But Wight is well acquainted with the idea of the tragic giant. Talking on the phone from Denver, a few hours before he crushes Chris Jericho's back in a ladder on Monday Night Raw, Wight says, "I catch shit from my wife every now and then. I start talking about how giants don't live very long, and she gets hot at me." He doesn't seem especially concerned about it.

***

If you read Jordan Conn's Roy Hibbert profile on Grantland a couple of months back, you learned a striking statistic: According to the Center for Disease Control, if you are seven feet tall and between the ages of 20 and 40 in the U.S., you are in very select company; there are fewer than 70 people like you. Ever since February, when he turned 41, Wight hasn't been one of the 70, but he's spent almost his entire professional life among their number. The WWE likes to call Wight "the world's largest athlete," and for all I know they're right. But he has competition.

If you're huge and athletic, you probably play basketball, the sport where all that height has the most obvious uses. Wight wanted to play basketball until he figured out that even giants need some vertical leaping ability. That hasn't stopped others, though. In NBA history, plenty of titans have soared (Wilt, Kareem, Shaq), and plenty others have become punchlines (Shawn Bradley, Hasheem Thabeet, Gheorghe Mureşan). And the giant failures often tend to be more interesting than their successful peers; just imagine a hangdog Bradley mooning around an NBA locker room, bumping Garth Brooks on his Discman, utterly failing to make any non-paralyzingly-awkward conversation with his teammates.

If you want to fall down a real Wikipedia hole, though, start looking into the seven-foot athletes who found their way to other sports. Consider, for example, the South Korean kickboxer and MMA fighter Choi Hong-man, or Pakinstani cricketer Mohammad Irfan. The 27-year-old, 7'1" pitcher Loek van Mil is the tallest professional baseball player ever, and he's currently playing for the Akron Aeros, one of the Cleveland Indians' AA farm teams. These are people who did strange things with their even stranger genetic birthrights.

When someone that tall enters competitive public arenas, their humiliations are that much more visible: Tracy McGrady bringing God's fire down on Shawn Bradley is a YouTube classic. So is the sight of Emelianenko Fedor submitting Hong Choi-man by grabbing an armbar and holding onto it for dear life, like a farmer hugging a tree limb in a tornado. But those moments of operatic mortification have nothing on sports' actual tragic-giant stories, which will make your heart hurt if you let yourself think about them. 7'2" Margo Drydek, the tallest player in WNBA history, dead at 37 after suffering a severe heart attack, while pregnant with her third child. 7'11" Romanian boxer Gogea Mitu, dead of tuberculosis at 21. Argentine pro wrestler Jorge González, who wrestled as the Giant González in the WWF and El Gigante in WCW, dead of diabetes at 44. In sports, as elsewhere, the tallest among us do not last. The human body was not meant to reach the heavens.

***

By most accounts, Bill Walton stands well over seven feet tall. But during his NBA career, Walton always insisted that he was 6'11" because he didn't want to be considered a freak. When I read that fun fact in David Halberstam's The Breaks of the Game, it hit a chord. I've been doing the exact same thing as Walton for my entire adult life. I'm not as tall as Walton. I'm not even one of the less-than-70 seven-footers in my age bracket in the U.S. But I'm close. Another quarter-inch, and I'd pass the seven-foot barrier. But anytime anyone asks my height, I say that I'm 6'11". I don't mention the extra three quarters of an inch. People don't need to know about that.

In any case, I'm still pretty fucking tall. And being pretty fucking tall is a weird thing to wrap your head around.

In my life, I've met four people taller than me, and I remember each one of them vividly. The one guy outside the bar in Baltimore who wanted to talk about the Gaslight Anthem. The backup center for the Syracuse Orangemen, who I saw around campus for four years and then only talked to when I drunkenly photobombed him during a graduation party. The frighteningly skinny African man with the two chipped front teeth who stood in front of me in line at a Seattle coffeehouse. The goateed yokel who, in a cruelly appropriate twist of fate, ended up standing directly in front of me during the Ramones' set at the West Virginia stop of Lollapalooza 96. Every time I met one of them, I felt a sharp wave of vertigo. The experience of looking up to talk to somebody just felt so completely alien every single time. Looking up is not a thing that I do.

When you're this tall, it becomes a deeply entrenched part of who you are. You become separate, or at least you think of yourself that way. At loud parties, you need to find a stool if you want to hear anything anybody says; otherwise, you're a disembodied head floating a foot above the crowd. Your clothes will not fit as well as other people's clothes, and you will be acutely aware of that fact at all times. In certain American cities, large crowds of children will just bust up laughing when they see you coming. (Baltimore, you are forever my home and I love you, but sometimes fuck you.) And if you spend enough time looking at the Wikipedia pages of past famous giants, you will start to think of yourself as doomed.

On the other hand, people remember your name, it's easy to get bartenders' attention, and you can almost always see well at concerts, though your sightlines usually come at somebody else's expense. It's a bargain that your genetics made for you.

***

Paul Wight, bless him, seems to think of his massive size as a gift from God, not a devil's bargain. There was a moment earlier this year when Wight was rumored to be fighting Shaq at this year's Wrestlemania. If that had happened, it would've been the collision of the two most genially cartoonish giants in sports, the two guys who come off most like enormous eight-year-olds. I wanted to talk to Wight for this piece because, among the giants I've seen on TV, he seems the least tortured by his height. After all, he's voluntarily spent the last 17 years in a grandly ridiculous, mortally dangerous line of work -- strapping on his comic-book caveman singlet and pretending to fight hulking musclemen across the globe, risking crippling injury every time he lets one of them lift him.

There are plenty of reasons why I could never do what Wight does. Even though we're nearly the same height, he weighs more than two of me. And the two afternoons I spent in a pro-wrestling training ring a decade ago taught me how much it hurts to wake up the morning after you've been learning to theatrically flop on canvas. But mostly, I've never been able to imagine performing my height. I've gotten used to people staring at me, but I've never learned to like it. I played basketball in high school, but I sucked at it, and hated sucking at it. I never bothered to learn how to play the game effectively beyond the obvious lumbering rebounds and shot-blocks. I fouled out of games on purpose if I was in a bad mood. I told myself that I wanted to do something with my brain and not my body, like that was even my choice to make, or like there was any real divide. So now I'm a writer, and I spend entire days living in my own head, only leaving to take my dog on walks or to take my kid to the park. Truthfully, I was too lazy and too self-conscious to ever do jack shit athletically. I'm a writer because it's what I've always wanted to be, but god knows my height probably had something to do with that desire. Pro wrestling is pretty much the opposite of anything I could ever do. I am not like Paul Wight.

***

Wight's always been huge. By his own estimation, he was nearly five feet tall at five years old. But he looks comfortable in his skin, and he says that he's been at peace with it ever since high school. "There was some awkwardness to it when I was very young, but I came to rely on it, to make it a strength," says Wight. "I embraced my size."

He's not wrong. For the past few generations of wrestling fans, Wight has been an affable constant, one of the few guys who never goes away. Wrestling lore is filled with giants like the Great Khali and the Giant Silva and Kurrgan, massive human redwoods who had a few memorable moments but who faded into the background as soon as everyone realized they couldn't really wrestle. Wight can wrestle, and he can do all the intangible non-wrestling things that pro wrestlers need to do. He can loom. He can glare. He can act, after a fashion. He can, when necessary, abase himself, or mercilessly mock himself. He can grow a mean mullet. He can convincingly appear to get his ass beat by Floyd Mayweather at Wrestlemania.

When Wight realized that the NBA wasn't going to work out for him, he spent a few years working civilian jobs: "I was a used car salesman for a little while in Wichita, Kansas, and I answered the phones for a company in Chicago called Jusco Karaoke. I tried to be a door-to-door salesman for State Chemical Manufacturing; that didn't work out." But he's always been a wrestling fan, and after a meeting with Hulk Hogan, he finally found a way to break in. In his first-ever match in 1995, he beat Hogan for the WCW World Championship. He's been around ever since.

Many of the vocal internet fans of pro wrestling love to hate Wight, since he regularly obliterates their underdog favorites and since he never busts out the same spectacular moves as his smaller peers. But to hear Wight describe it, his vast and glacial ring presence is something he had to learn: "When you have size and ability, you can't do all the things that you're capable of because it just doesn't make sense. Yeah, I can do a moonsault, I can do a dropkick off the top. But a lot of these moves, the promoters will tell you that it just doesn't make sense for our industry. You're supposed to be a big guy, stand in the middle, let people bounce off of you. When I was starting out in the industry, my size was an attraction, and I wanted to be an athletic attraction. I wanted to wrestle as hard as the other guys. But visually, it just doesn't look right for the big guy to do the same things as the smaller guys. Our business is to entertain, so I had to learn a role and fill that role."

I mention last year's Survivor Series. During a match against the former Olympic weightlifter Mark Henry, Wight climbed to the top rope and then jumped off, hitting Henry with a titanic diving elbowdrop. But before leaping, Wight teetered on that top rope for a few seconds, looking like he was having second thoughts about what he was about to do. It's exactly how I imagine I'd look if I found myself on the top rope. "That was all drama," says Wight. "If I just walked up there and made it look easy, it wouldn't be as dramatic as it was."

***

Wrestlers have long histories of dying young, of suffering debilitating injuries, of finding it impossible to make their personalities translate on the required grand scale. Wight has endured, and along with Andre the Giant, he's really one of only two giants in pro-wrestling history who can claim that.

Andre was, of course, most famous giant in wrestling history. Andre owed his size to acromegaly, the pituitary condition that ultimately led to his death. Wight was also born with acromegaly, but it doesn't look like it's going to kill him. When Wight was 19, he went into the Mayo Clinic for surgery to keep him from growing further. He apparently suffers no further ill effects from the condition. (Other famous acromegaly cases: The Addams Family star Ted Cassidy, two-time James Bond bad-guy henchman Richard Kiel, Tony Robbins, possibly Abraham Lincoln.) Wight's fellow current WWE giant, the 7'1" Great Khali, also has acromegaly, and he just had his own height-ending surgery.

According to Wight, it helps that he works with the WWE's crack medical professionals at his disposal. But I still hear plenty of black humor coming through when he's talking about his acromegaly: "I'm actually doing really good. Unless I walk out in front of a bus -- a really big bus -- I have the chance to live a really good life... I'd like to live to be the first old giant. That would be cool."

***

My son was born a month ago, and he is going to be tall; there's no getting around it. My wife is six feet tall, and my height combined with hers is a genetic combination that practically guarantees tower status. He could be taller than me. I feel a little bit sorry for the guy.

Wight has kids, and they're tall. But they're not freaky-tall; they're regular-tall. I ask him if he was ever worried about passing his size onto his kids, and he gives me a sitcom-dad line about fearing the day his daughter starts to date.

Wight's wrestling career has been exceptionally long and important, and that's amazing. But what's even more amazing is that he seems to be a rare beast: A giant with absolutely no evident self-consciousness, no crippling constant awareness that he is not like others. For a select few of us, that makes him an inspiration.